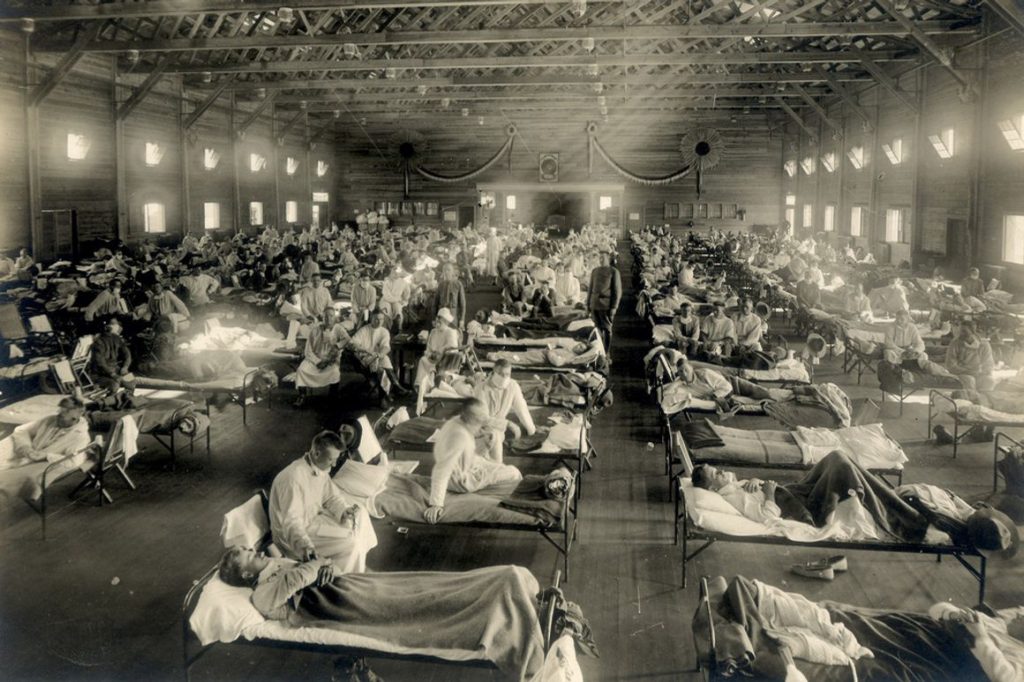

Emergency hospital during influenza epidemic, Camp Funston, Kansas, 1918. (Photo: National Museum of Health and Medicine)

In the fall of 1918, U.S. Army and Navy medical officers in camps across the country presided over the worst epidemic in American history. During this time, The War Department operated approximately 40 airfields for aviator training, most were located near large basic training facilities.

During WWI, flying was a dangerous profession, whether in combat or not. Thus, Army Air Corps hospitals were established near the flying facilities. In 1918, this included the Army flying fields at Grays Harbor in Washington, Crissy Field at the Presidio of San Francisco, and when Rockwell Field in San Diego moved to Riverside, March Field. These were located near the three large training facilities on the West Coast; Fort Lewis in Washington, and Camp Fremont and Camp Kearney in California.

The virus traveled with military personnel from camp to camp and across the Atlantic, and at the height of the American military involvement in the war, September through November 1918, influenza and pneumonia sickened 20% to 40% of U.S. Army and Navy personnel. By the War Department’s most conservative count, the pandemic sickened more than one million military men and killed almost 30,000 just in the United States. Thus, during the influenza outbreak, the number of hospital beds in these facilities multiplied by 12-fold.

Aviators at the training bases had a high rate of accidents, and only the best and most experienced were sent to Europe for WWI. In his 1919 report, the Secretary of War stated “the casualties in the air force were small compared with the total strength, the casualty rate of the flying personnel at the front was somewhat above the Artillery and Infantry rates. The results of allied and American experience at the front indicate that two aviators lose their lives in accidents for each aviator killed in battle.”

Thus one can imagine the rate of accidents at the Air Corps training facilities in California. Statistics showed that among then candidates for the Air Services during WWI, as many as 50% developed neuroses during training.

Figures also showed that among the graduate pilots, 90% of the casualties were the results of defects in the physical condition of the pilots themselves.

The standards for examination of potential pilots were established and revised in 1917 by colonels Lyster and Jones, the term “Flight Surgeon” came into popular use in March 1918, and in August 1918 Maj. Ream became the first flight surgeon to die in an airplane crash; Ream Field in Imperial Beach, just south of San Diego, is named after him.

Eventually, flight medicine became a full branch of medical study as research studied the psychological effects of combat flying as well as the physiological aspects.

Even from the early days of WWI, it was noted that the injuries were different from the other sections of the military. For example, most of the injuries from aircraft were to the head and spine, from which few survived, and even fewer recovered. Rehabilitation of military patients was also revised by the observations of flight surgeons.

Lt. Col. Rusk introduced active rehabilitation into U.S. Army Air Corps hospitals. He observed that during convalescence boredom was rampant and that on discharge many soldiers could not return to duty and frequently required further medical care. Rusk realized that military medicine was different from civilian medicine.

“From a military point of view, you were either a patient or a soldier. If you were a soldier, it meant you got full duty with whatever that involved, perhaps a 10-mile hike with full pack. … It seemed obvious to me that men did not get ready for full duty by playing blackjack or listening to the radio.”

Thus, the lessons learned over the last century of military medicine has brought us from the Air Corps hospitals of the 1918 influenza pandemic, to the modern practices of treating military personnel at the Veterans Administration hospitals for the COVID-19 pandemic of today.

Endnotes

1 Byerly, C., “The U.S. Military and the Influenza Pandemic of 1918–1919,” Journal of Public Health Reports, National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD, 2010; 125 (Suppl 3): 82–91, PMCID: PMC2862337.

2 United States War Dept, “Annual Report of the Secretary of War,” U.S. Government Printing Office, 1919, p. 55.

3 Johnson, M., “The History and Development of Aviation Medicine,” Journal of the National Medical Association, November 1943, pages 194-199.

4 Dillingham, T., and Belandres, P., “Physiatry, Physical Medicine,and Rehabilitation: Historical Development and Military Roles,”Volume 1, Chapter 1, page 5; URL: https://ke.army.mil/bordeninstitute/published_volumes/rehab1/RH1ch1.pdf, accessed 7 July 2020.